TULLIALLAN, like the adjoining parish of Culross, formed a detached portion of Perthshire; but by the rearrangement proposed by the Boundary Commissioners, and confirmed by an Order in Council, dated 23rd February, 1891, it also was separated from Perthshire and added to Fife. It lies immediately to the west of Culross, and is bounded on the west and north by Clackmannan, and on the south and south-west by the Firth of Forth. Its utmost length from north to south is three and three-quarter miles, and at no part does it exceed three miles in breadth. The two lochs of Pepper Mill Dam and Tulliallan Water are fed by small rivulets which rise in Clackmannanshire and in Culross parish, and they find an exit to the Forth by an inconsiderable stream that flows into the river near the town of Kincardine. In early times the parish consisted only of the estate of Tulliallan ; but in 1659 the boundaries were altered so as to include the barony of Kincardine and the estates of Lurg, Sands, and Kellywood, which had formerly been in Culross parish. The population of the parish has fluctuated very considerably during the present century, as the following figures will show:-(1801) 2800; (1831) 3550; (1861) 2410; (1871) 2184; (1881) 2207; (1891) 2177. The shore is for the most part level, but the ground rises towards the north in the form of a broad-based hill, which attains a height of 325 feet, and then slopes towards the north in gentle undulations.

TULLIALLAN, like the adjoining parish of Culross, formed a detached portion of Perthshire; but by the rearrangement proposed by the Boundary Commissioners, and confirmed by an Order in Council, dated 23rd February, 1891, it also was separated from Perthshire and added to Fife. It lies immediately to the west of Culross, and is bounded on the west and north by Clackmannan, and on the south and south-west by the Firth of Forth. Its utmost length from north to south is three and three-quarter miles, and at no part does it exceed three miles in breadth. The two lochs of Pepper Mill Dam and Tulliallan Water are fed by small rivulets which rise in Clackmannanshire and in Culross parish, and they find an exit to the Forth by an inconsiderable stream that flows into the river near the town of Kincardine. In early times the parish consisted only of the estate of Tulliallan ; but in 1659 the boundaries were altered so as to include the barony of Kincardine and the estates of Lurg, Sands, and Kellywood, which had formerly been in Culross parish. The population of the parish has fluctuated very considerably during the present century, as the following figures will show:-(1801) 2800; (1831) 3550; (1861) 2410; (1871) 2184; (1881) 2207; (1891) 2177. The shore is for the most part level, but the ground rises towards the north in the form of a broad-based hill, which attains a height of 325 feet, and then slopes towards the north in gentle undulations.

The town of Kincardine-on-Forth, the only populous place in the parish, is situated in a position which ought to have made it of great commercial, importance. It has an excellent roadstead; and as the Forth is only half-a-mile wide at this spot, the ferry was at one time the main communication between Kinross-shire district and the southern shore. During last century a great development of the shipping took place at Kincardine, for it is stated in the Old Statistical Account that, whilst there were only five boats from 10 to 20 tons burden belonging to the town in the beginning of the century, by 1740 there were no less than 30 vessels connected with the port from 15 to 60 tons burden, with a total tonnage of 860. Shipbuilding was carried on for some time here with great success. In 1786 there were nine vessels on the stocks at one time, and the Kincardine vessels then registered were 90 in number, with a tonnage of 5461-considerably, more than Alloa then possessed. The decline in trade began through the stopping of some of the coal mines in the district, the abandoning of the salt pans, and the shutting up of some of the thriving distilleries in the neighbourhood. Referring to Kincardine, Mr David Beveridge says, in his valuable work on Culross and Tulliallan “The present town was in great measure created by the shipbuilding trade, which attained a wonderful prosperity in the end of the last and the beginning of the present century, and engrossed the industry of the inhabitants so much that a cursory perusal of the inscriptions in the burying-ground adjoining the old church of Tulliallan would lead the visitor to the conclusion that almost every person in Kincardine had been a shipowner. Now the trade has entirely disappeared, and scarcely a vessel is to be seen at Kincardine, except a few lying off in the roadstead that have come up there with cargoes of wood, or occasionally grain, preparatory to their being conveyed by means of lighters to Alloa. A woollen factory, a rope and sail work, and a large paper mill constructed out of the once famous distillery at Kilbagie, about two miles distant from the town, are the only sources of employment for the inhabitants in the way of trade and manufactures. The Forth Paper Works at Kilbagie, referred to by Mr Beveridge, are situated outside the parish, and are in the County of Clackmannan. The salmon fishing in the Forth also gives employment to a number of the inhabitants of Tulliallan parish. An attempt was made to restore the importance of Kincardine by the improvement of the harbour many years ago; but the development of the railway system has left the town outside of the great lines of traffic and commerce. In 1823 and 1839 two embankments were erected on the west and east sides of the town for the purpose of reclaiming land from the Forth. The bank on the west side is 11 feet high and 2020 yards long, and by it 152 acres were reclaimed at a cost of £6104.

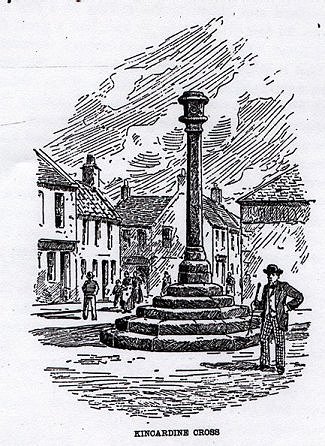

The eastern embankment is 16 feet high and 3040 yards long. It cost £14,000, and by it 214 acres were reclaimed. Kincardine is a burgh of barony under the control of three bailies. The only noteworthy antiquity in the town is the Market Cross, which stands in an open space in the centre of the burgh. It is an elegant Corinthian pillar, nearly nineteen feet high by four feet in circumference, raised on a graded base, and bearing the arms of the Earls of Kincardine carved on the capital. Though there is no date upon it, there is every probability that it was erected in the middle of the seventeenth century.

The ruined castle of Tulliallan is situated about a mile to the north of Kincardine, within a well wooded park, and commanding a magnificent view of the Carse of Stirling. It is supposed that the waters of the Forth flowed near its walls at one time, though the work of reclamation has transferred it inland. Even in its decay the castle presents many tokens of its having been one of the finest structures of its time in some respects. A detailed description of the ruin, with numerous illustrations, will be found in Messrs Macgibbon & Ross’s “Castellated and Domestic Architecture of Scotland” (vol. i., page 550). Referring to the castle, these writers say it has been designed as a pleasant residence rather than a place of strength, and thus shows more elegance and taste in its architecture than is usual in the great but gloomy castles of the time. This is well illustrated by the fine vaulting of the ground floor, which surpasses anything of the same kind to be met with in any similar building in Scotland. At the same time, defence was not lost sight of. The principal entrance has been approached by a drawbridge, the recess for which, together with the aperture for the chain and the chamber for the windlass, are all well preserved. This entrance was also protected by a portcullis, and there are apertures or machicolations over both this door and the postern at the east end by which missiles might be thrown on assailants who might have penetrated through the outer doors. The ground floor was divided into two apartments, both beautifully vaulted with groined and ribbed arches resting on a row of central Pillars. The smaller of these apartments, 25 feet 6 inches by 22 feet, had a great fireplace with moulded jambs and large projecting hood. The distinctive architectural features of the fireplace are so decidedly Early English that it might at first be imagined that the building belonged to the thirteenth century; but an examination of other portions of the structure proves that Tulliallan is not older than the fifteenth century. The moulded sconces for lights at each side of the chimney are rare features in Scotland, though not uncommon in France and England. The windows of this room are of unusual size for a ground flat, and have trefoil arched heads and stone seats in the recesses. The small wing at the north-east corner was probably intended both as a garderobe and as a flanking tower for defence. The other apartment on the ground floor, which is 37 feet by 22 feet, seems to have been used for stores, as it has no fireplace, and only small square openings for windows. The projecting north-west wing with separate staircase was probably the cellar, but might also be used for purposes of defence. The upper floor contained the great hall, 38 feet by 22 feet 6 inches, and private hall, 21 feet 6 inches by 22 feet 6 inches, with a bedroom off it over the cellar. A staircase contained in the projecting octagonal tower between the two latter rooms leads down to the cellars and upwards to the floor above. A peculiar feature connected with the common hall is an outside entrance door on the first floor level. This was probably reached by an outside stair of some temporary kind, which might be removed in case of attack. This arrangement would make it unnecessary to lower the drawbridge and open the principal entrance doorway except on special occasions. It also explains why the main staircase led to the private hall instead of, as usual, to the common hall, as without the above separate entrance all the traffic to the hall would have passed through the private room, which would have been very inconvenient. The mansion seems to have been enlarged, probably in the sixteenth century, when the north-east wing was doubled in size, and carried up several storeys so as to provide bedrooms. The house was surrounded with a rectangular enclosure with a ditch and mound, the latter no doubt palisaded, traces of which are distinctly visible.

The name of the builder of Tulliallan Castle is not certainly known. The place was long in the possession of the Blackadders, but there are so many errors in the received genealogy of that family that it must be accepted with caution. The following account of Tulliallan and its proprietors is founded upon an examination of numerous charters connected with the estate, and may be received as authentic.

The first family name found associated with Tulliallan in deeds and charters is that of Edmonstoun. David Edmonstoun of Ednam, in Roxburghshire, died previous to 1426, leaving his son James a minor. In course of time James Edmonstoun succeeded to and acquired extensive estates in various parts of Scotland. He became Edmonstoun of that Ilk, purchased the estate of Boyne, in Banffshire, and also Tulliallan, though the name of the previous proprietor of the latter place is not recorded. In his later years he was designated “of Tulliallan,” and it is therefore likely that he had a manorial residence on the estate, though it is improbable that he built the castle of which the ruins remain. At his death in 1485 James Edmonstoun left only two daughters, Elizabeth and Margaret, both of whom were then married, and the estates were divided in equal portions between them, Elizabeth was married to Sir Patrick Blackadder, son of Robert Blackadder of that Ilk, in Berwickshire; while the husband of Margaret was Walter Ogilvy, a scion of the Ogilvys of Airlie. By a charter dated 1485 an arrangement was made whereby Elizabeth Edmonstoun resigned her share in the estate of Boyne in exchange for Margaret’s share of Tulliallan, and thus the two families of Ogilvy of Boyne and Blackadder of Tulliallan were founded. By a curious error the famous Robert Blackadder, first archbishop of Glasgow, and founder of the part of Glasgow Cathedral known as Blackadder’s Aisle, is repeatedly described by historians

as the son of Sir Patrick Blackadder and Elizabeth Edmonstoun. But in the charter whereby the Archbishop founded the Chapel of St Kentigern, near Culross, Sir Patrick is distinctly designated the brother-german of the Archbishop. The confusion has arisen possibly from the fact that the younger son of Sir Patrick was Magister Patrick Blackadder, who was archdeacon of Glasgow. The only other son of Elizabeth Edmonstoun was John Blackadder, to whom she resigned the succession of the estate of Tulliallan in 1487. Sir Patrick Blackadder died in 1507, and after his death his son the Archdeacon gave over all claims he had upon Tulliallan to his brother, John Blackadder. The charter by which this resignation, was effected is noteworthy as containing the earliest documentary reference to the Castle of Tulliallan. This almost decidedly shows that Sir Patrick Blackadder was the builder of the structure. Still further to confirm this theory, it will be found on examination that the peculiar style of the vaulting in the castle, to which Messrs Macgibbon & Ross refer, is an adaptation of the vaulting found in Blackadder’s Aisle at Glasgow Cathedral. This evidently suggests that the workmen whom the Archbishop had employed at Glasgow were sent to build his brother’s Castle of Tulliallan, and possibly also the Chapel of St Kentigern at Culross. No other theory will sufficiently account for the unique form of vaulting adopted at the castle, which is without a parallel in Scottish domestic architecture.

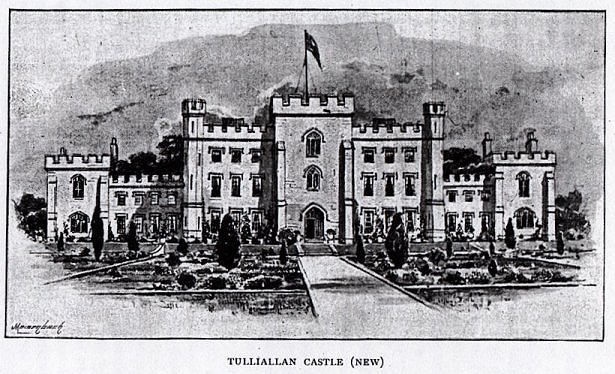

John Blackadder of Tulliallan succeeded to the estate of Tulliallan in 1507, and in 1529 he resigned the lands to his son John. It was a fortunate circumstance for the family that he did so, as in 1530 he was tried and executed for the murder of the Abbot of Culross, and in the ordinary course his lands would have been forfeited to the Crown. John Blackadder, junior, was then a minor, under the tutelage of his mother’s brother, and in 1531, with the consent of his curators, he sold the Overtoun of Tulliallan to his uncle, Robert Stewart, in Dunfermline. In 1544 John Blackadder married Margaret Halkerston, and in 1551 the lands were confirmed to them by Queen Mary. He had espoused the cause of the unfortunate Queen, and accordingly, while preparations were being made by the Regent Moray to take the field and begin the campaign which terminated at Langside in May, 1568, the Privy Council ordered that John Blackadder should resign to the Regent “the castell, tour, and fortalice of Tulliallane.” By some means he succeeded in escaping the dangers of the situation, and was still laird of Tulliallan in 1578. His brother, Patrick Blackadder, parson of Tulliallan, was one of the firebrands of the time, and his name frequently appears in the records of the Privy Council as the defender in actions for assault and riot. John Blackadder was succeeded by his son James, whose name first appears as laird of Tulliallan in 1551 and who was in possession of the estate in 1605. He was the last of the race to hold the estate, and shortly after this date it was acquired by Sir George Bruce of Carnock. Early last century the baronies of Tulliallan and Kincardine were purchased by Colonel Erskine, who was succeeded by his son, John Erskine of Carnock, the famous jurist. The latter bequeathed Tulliallan and Cardross to James Erskine, the eldest son of his second marriage with Miss Stirling of Keir. James Erskine’s son, David Erskine of Cardross, was married to a daughter of John, Lord Elphinstone, and his wife’s uncle, the Hon. George Keith Elphinstone (afterwards Baron Keith), purchased the estate of Tulliallan from David Erskine in 1798. Lord Keith (born 1747, died 1823) attained the rank Admiral of the Blue, was created a peer of Ireland with the title Baron Keith of Stonehaven Marischal, and advanced to the dignity of Viscount Keith in 1804. By his first marriage with Miss Mercer of Aldie, he had one daughter, the Hon. Margaret Mercer Elphinstone, who succeeded, in terms of the patent, to the barony of Keith, though the other titles became extinct. Lord Keith’s second wife was Hester Maria, daughter of Mrs Thrale, the friend of Dr Samuel Johnson, and by her he had one daughter, the Hon. Georgina Augusta Henrietta, who was married first to the Hon. Augustus John Villiers, son of the Earl of Jersey, and secondly to Lord William Godolphin Osborne, brother of the eighth Duke of Leeds. By his will Lord Keith devised the estate of Tulliallan to his two daughters successively; and after the death of the Baroness Keith, the elder daughter, in i1867, it fell to Lady W. Godolphin Osborne, whose husband had assumed the additional name of Elphinstone. She died in March, 1893, but as the estate reverts to the representative of the elder daughter of Lord Keith, it is now in the Possession of Lady Keith’s son, the Marquess of Lansdowne. The modern mansion of Tulliallan was erected by Viscount Keith in 1818, and stands a short distance to the south-cast of the old castle, and close beside the town of Kincardine. Long before its erection the castle had been abandoned, and it is likely that no one has resided in it since the last of the Blackadders departed this life, as later proprietors had mansions elsewhere. In 1722 the castle was described as a ruin. The present estate of Tulliallan is very much larger than that which belonged to the Blackadders, as additions were made to it by the purchase of adjoining properties both by the Erskines and the Elphinstones.

The estate of Sands, which has been in the possession of the Johnstons Of Sands for over a century and a half, is now the property of Laurence Johnston, Esq. It is situated to the north of Longannet Point, and includes the farms of Sands Home Farm, Blalowan, and Cockmuirhall, and the quarry of Kelliewood. A portion of the estate of Airthrey, belonging to Lord Balfour of Burleigh, lies within Tulliallan parish, and includes Gartarry and Hartshaw and the quarry of Brucefield. At Bordie, on the main road to Kincardine, the ruins of the old mansion of the Bruces of Bordic may still be seen.

Note: many spelling mistakes in this document are faithful copies from the actual document. These may or may not reflect accepted spellings at the time the document was prepared.

For more information about any of the topics contained in this web page please contact: Kincardine Local History Group